Does My Child Stutter? Using SALT to assess stuttering and measure outcomes

Does My Child Stutter? Using SALT to assess stuttering and measure outcomes

Published at: 2020-03-10

Stuttering is a childhood-onset disorder of speech fluency that has an incidence of ~5% in preschool age children and a prevalence of ~1% in adults (Bloodstein & Ratner, 2008). For most children, stuttering begins between the age of 2-5 years (Guitar, 2019). With the relatively high incidence of stuttering, it is more than likely that a SLP working with pre-school age children will have a few children on their case load who stutter or are at least suspected to stutter. Research shows that there is a higher incidence of phonological disorders in children who stutter (CWS); however, reports on language skills and stuttering are mixed, i.e. some studies show that there is a higher incidence of language disorders among CWS, and some do not show a difference (Bloodstein & Ratner, 2008; Guitar, 2019). As a clinician, it is important to complete a thorough evaluation of every child on your caseload for language skills, phonological skills, and fluency. This is where SALT comes in. If you are already using SALT to measure language outcomes, it is very easy (and highly recommended) to also keep track of fluency. So, how does one go about making sure that they are adequately measuring fluency along with language skills in SALT? A few simple steps based on two scenarios.

Scenario 1: Child does not stutter, or no one has reported concern about stuttering

If parents do not report concerns and you do not suspect stuttering, make sure to transcribe carefully to make sure you are marking all mazes correctly. Mazes overlap with stuttering to a large degree (more on that in a bit). Remember, stuttering begins between 2-5 years of age for most children. Documenting the mazes correctly from the first evaluation will ensure you have good data for a fluency assessment later if you need it. So, why be careful about correctly documenting all mazes? Simple: there is a lot of overlap between mazes and stuttering (Byrd, Bedore, & Ramos, 2015). While the majority of mazes are considered “typical disfluencies” (TD) some mazes are considered as stuttering-like disfluencies (SLD). These include:

- Repetition of sounds (e.g. I*I*I would like ice-cream)

- Repetition of single syllable words (e.g. we*we*we would like to go to the pool)

- Repetition of a sound or part of a word (e.g. Wh*wh*wh*where is the hummus?)

- Some part-word revisions (e.g. I want a c*ball) can be stuttering, especially if it is accompanied with tension (either facial muscles or voice)

- Some filled pauses (e.g. (um)) can be part of stuttering (often used as an avoidance before a stuttering moment)

A sample SALT transcript coded for disfluencies: scenario 1

C (Um the um) the frog was in the jar. C Then the boy and the dog was[EW:were] sleep/ing. C (And) and the frog jump/ed out of the window. C (The) the (um b*) boy and the dog look/ed (for um) for the frog. C And he could/n’t find the frog. C And (um the w* with) with the jar it was too heavy.

As you can see, if we are careful about how we transcribe, we can easily get a preliminary measure of how many SLD’s are present in the child’s speech. For monolingual English-speaking children, more than 3 SLDs per 100 words (i.e. 3%) warrants a comprehensive stuttering evaluation (Yairi & Ambrose, 2005). For a child who is already on your caseload, if the parent reports concern with the child’s fluency and/or you have concerns about his fluency, looking at mazing at a granular level as described above is a great first step. However, is that enough to make a diagnosis and recommendation? No, this is where we need to discuss Scenario 2.

Scenario 2: Child stutters or parents report concerns about stuttering

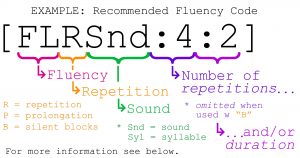

In the event you have a new child on your case load and there are fluency concerns (either raised by parents or based on your initial evaluation), how do we proceed then?  Irrespective of whether the child has been referred for language or fluency, it is important to assess language, phonology, and fluency. If you are already proficient with SALT and have been using it for language sample analysis (LSA), all you need to do is to familiarize yourself with the SALT Fluency codes and make sure to insert the fluency codes in your transcript! My only caution here is to make sure that you are measuring how many times a sound or part-word is repeated (e.g. r*r*r*r*rain is coded as: “[FLRSnd:4]rain”, indicating that the sound (FLRSnd = repetition of sound) is repeated 4 times. In case of a block, always make sure to count the duration of the stuttering event (e.g. “I saw a [FLB:3]rainbow” indicates 3 second block at the beginning of the word). One final recommendation, while not in the description of the SALT fluency codes, I also strongly recommend measuring the duration of sound/syllable repetitions in addition to how many times they were repeated. We can simply define this feature in SALT and add to the code, e.g. It is [FLRSnd:4:2]raining. Here, the code used, FLRSnd indicates it is a sound repetition. The first number FLRSnd:4:2 indicates the sound /r/ was repeated four times. The second number [FLRSnd:4:2] indicates the stuttering moment lasted for 2 seconds. Last but not the least, also make sure to code for concomitant behaviors. It is especially important to listen for pitch changes in children when they experience stuttering moments as those are indicative of tension in the vocal folds. Presence of physical concomitants is often an indicator of severity and we need that information to make a diagnosis of stuttering severity.

Irrespective of whether the child has been referred for language or fluency, it is important to assess language, phonology, and fluency. If you are already proficient with SALT and have been using it for language sample analysis (LSA), all you need to do is to familiarize yourself with the SALT Fluency codes and make sure to insert the fluency codes in your transcript! My only caution here is to make sure that you are measuring how many times a sound or part-word is repeated (e.g. r*r*r*r*rain is coded as: “[FLRSnd:4]rain”, indicating that the sound (FLRSnd = repetition of sound) is repeated 4 times. In case of a block, always make sure to count the duration of the stuttering event (e.g. “I saw a [FLB:3]rainbow” indicates 3 second block at the beginning of the word). One final recommendation, while not in the description of the SALT fluency codes, I also strongly recommend measuring the duration of sound/syllable repetitions in addition to how many times they were repeated. We can simply define this feature in SALT and add to the code, e.g. It is [FLRSnd:4:2]raining. Here, the code used, FLRSnd indicates it is a sound repetition. The first number FLRSnd:4:2 indicates the sound /r/ was repeated four times. The second number [FLRSnd:4:2] indicates the stuttering moment lasted for 2 seconds. Last but not the least, also make sure to code for concomitant behaviors. It is especially important to listen for pitch changes in children when they experience stuttering moments as those are indicative of tension in the vocal folds. Presence of physical concomitants is often an indicator of severity and we need that information to make a diagnosis of stuttering severity.

A sample SALT transcript coded for disfluencies: scenario 2

C (Um the um) the frog was in the jar. C Then the boy and the dog was[EW:were] sleep/ing. C (And) and the [FLP:01]frog jump/ed out of the window. C (The) the[FLR:2] (um) [FLRSnd:1]boy and the dog look/ed (for um) for[FLR:1] the frog. C And he could/n’t find the frog. C And (um the [FLRSnd:1]with) with[FLR:1] the jar it was too heavy.

This representative sample includes the fluency codes:

- FLP:01 This code is used to indicate prolongation of the initial sound of the word “frog” for a duration of 1 second.

- FLR:2 position at the end of the word “the” indicates that the entire word was repeated twice (also captured as a maze).

- FLRSnd:1 position at the beginning of the word “boy” indicates one repetition of the sound /b/.

- FLR:1 position at the end of “for” indicates one repetition of the word “for.”

- FLRSnd:1 position at the beginning of the word “with” indicates one repetition of the sound /w/.

- FLR:1 position at the end of “with” indicates one repetition of the word “with.”

Why is this important?

After you extract the fluency data and codes from SALT, you have all the information you need to make a diagnosis of stuttering severity. Irrespective of what standardized instrument you utilize, you will need a count of how many syllables (or words) were stuttered (i.e. SLD), what was the average duration of the stuttering, and the physical concomitants. SALT can be a very powerful tool if we input the correct codes with sufficient detail. With SALT, you can easily get data for a language and fluency assessment from the same sample and transcript. As with any other software, you will need to familiarize yourself with the fluency codes. To summarize, SALT provides a good overview of disfluencies and the possibility of stuttering when we correctly transcribe mazing behavior. However, if we suspect the child stutters, it is important to meticulously enter the fluency-specific codes to our SALT transcript so we can obtain a detailed report of all disfluency types, specifically stuttering-like disfluencies, to obtain a standardized stuttering severity score.

__________

SALT Resources:

PDF with a brief explanation of SALT's recommended fluency codes for printing can be found here: https://www.saltsoftware.com/media/wysiwyg/codeaids/Coding_Disfluencies.pdf A YouTube video quickly demonstrating how to insert fluency codes using SALT 20: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2QZ2oDbpeeU&feature=youtu.be For a more in depth look at custom coding, SALT offers a self-paced online course: https://www.saltsoftware.com/training/self-paced-online-training/course-1403-analysis-special-coding

References:

Bloodstein, O., & Bernstein Ratner, N. (2008). A handbook on stuttering New York. NY: Thomson-Delmar. Byrd, C. T., Bedore, L. M., & Ramos, D. (2015). The disfluent speech of bilingual Spanish–English children: Considerations for differential diagnosis of stuttering. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 46(1), 30-43. Guitar, B. (2019). Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment (5th Edition). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Yairi, E., & Ambrose, N. G. (2005). Early childhood stuttering for clinicians by clinicians. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed, Inc.

No Comments yet. Be the first to comment.